Saundarya Lahari

Saundarya Lahari

SAUNDARYA LAHARI - VERSE 22

- Details

- Written by Patrick Misson

- Parent Category: Content

- Hits: 33416

SAUNDARYA LAHARI

VERSE 22

KEY VERSE

A REVERSIBLE EQUATION

भवानि त्वं दासे मयि वितर दृष्टिं सकरुणां

इति स्तोतुं वाञ्छन् कथयति भवानि त्वमिति यः ।

तदैव त्वं तस्मै दिशसि निजसायुज्य-पदवीं

मुकुन्द-ब्रम्हेन्द्र स्फुट मकुट नीराजितपदाम्

bhavani tvam dase mayi virara drstim sakarunam

iti stotum vancham kathayati bhavani tvam iti yah

tadaiva tvam tasmai disasi nija sayujya padavim

mukunda brahmendra sphuta makuta nirajita padam

"O Goddess, you, on this your servant, bestow a kind look"

Thus intending to adore, no sooner one begins saying: "O Goddess, you..",

You grant him that state of identity with you,

The same as what Vishnu, Brahma and Indra accomplished by the waving of the bright lights on their diadems.

.

Prayers can be of different grades of efficacy or word content. Ritual actions of different kinds are also implied in the act of offering adoration or prayers to divinities or gods. An effective prayer is that which establishes the most direct bipolar contact between the supplicant and the god that is being addressed. The gods themselves represent different grades of values, according to the taste or understanding of the seeker. Compatibility between the counterparts of worshipper and worshipped, we see here, is the first and foremost condition for efficacy in prayer. In other words, prayer is like an interaction in chemistry or an equation in mathematics where there is a kind of osmotic interchange of values taking place. It could be likened to a mathematical equation. There are also many instances of reversible reactions and retroactive processes known in thermodynamic systems or in the context of cybernetics. Semantics and logistics also conform to a system in which there is a reciprocal exchange of meanings taking place inter-physically and trans-subjectively. Such are some of the subtle structural implications to be kept in mind in order to understand the meaning of this verse.

In the first place, we have to remember that it is not just an ordinary goddess who is the object of adoration here, but it is the ultimate value in the Advaitic context that is being adored. The person fit for such an exalted and pure form of worship must also conform to certain requirements in himself. He is not to be treated as a mere upasaka (a worshipper only paying lip service), who understands the dead letter better than the living word, due to his lukewarm or hidebound attitude, and who lacks wholeheartedness because he is too full of personal outward interests to keep his soul from entering the vertical, subtle eye of the needle.

The bipolarity between worshipper and worshipped cannot become fully established, except on a homogeneous ground where these two counterparts participate on equal terms. This homogeneous ground is called worship. Here the worship is an osmotic interchange between the inner stuff of existential and essential factors. With the Goddess visualized existentially, the supplicant is to be her dialectical counterpart, in terms of the subsistent, with the overall situation of worship being the value factor, where the two counterparts cancel out in the glory of the Absolute. The worshipper and the worshipped enter into equal partnership here as interchangeable factors. The thinnest medium through which this partnership can take place is where words meet the meaning corresponding to their form. This cybernetic or thermodynamic equilibrium could also be thought of as taking place in the thinner semantic world where words and meanings circulate between subject and object, or self and non-self. Such equilibrium is called homeostasis.

In the pure world of non-duality there is reversibility of reaction, as in an equation expressing the same in algebraic terms. There is also a similar one-to-one correspondence and cancellation in a more subtle domain. Whether in the world of logic or intentionalities, prayers are judged more by the intention implied in them than by the syntactical or pragmatic aspects of the words in which the prayers are clothed.

In Advaita Vedanta it is granted that God and man are the same. If a god-like man waves lights to propitiate a god, it is quite natural to reverse the position and say that, when such a worthy man humbles himself, the god also decides to wave lights to the personality of the supplicant in return. Thus full cancellation of counterparts occurs.

In the first line, though the prayer is only just begun, the Goddess is already willing to respond to the intention present. It is only for a kind look, and not for any worldly benefit, that the supplicant here prays, because as an Advaitin or sannyasin, (renouncer) he has no other favours to ask for. Not only is the intention readily recognized, but the response is both total and spontaneous in bestowing not just a mere kind look. Partial stimulus produces total reaction of the counterpart, here contained within the word "you", as between interchangeable counterparts.

The Goddess seems to say: "You are not a mere worshipper, you are myself. There is an equality of status and richness of quality between us, because Advaita cannot countenance any shade of duality".

There is a reference in the last line to worship by the three gods, who are supposed to be far superior to human beings as custodians of the three phenomenal functions in the cosmological setup of the Absolute Universe. But, even if their worship should attain to its fullest benefit or merit; they, the most important agents in the phenomenal context of the universe, are here only given the same marks, when judged finally by effect, as the humble supplicant who stands outside the context of holiness or merit altogether. Vedantic worship is based on understanding rather than on ritualistic merits belonging to mere Vedism.

The reference to the lights on the diadems, which are supposed to function here as the flames used in the ritualistic waving of lights in temples to propitiate various gods, is to indicate that Vishnu, Brahma and Indra are doing their best from the standpoint of their own notions and value systems - as far as such values are within their grasp - to honour the Absolute Goddess. But in spite of such efforts, they only get pass marks on the final test, while the non-dualistic worshiper not only passes freely beyond such a point of perfection, but attains the worship of the Goddess herself. Such is the overwhelming beauty of this situation, to be understood in the overall context of intentionality.

The "identity with you" is only to be treated as a corollary to any one of the four well known mahavakyas (great sayings) of the Upanishads, each of which is an equation between the Self and the non-Self in the context of Absolute Wisdom.

Intentionality counts more than words. We would be justified in thinking that words themselves are finally extraneous to the situation from the last verse of the poem, where Sankara washes his hands completely of even having taken the trouble of writing these verses, politely excuses himself and withdraws from the scene of holiness.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS WITH STRUCTURAL DIAGRAMS RELATED TO THIS VERSE FROM SAUNDARYA LAHARI/NOTES.

Bhavani tvam - o Goddess, thou

Dase mayi - on this Your servant

Vitara - bestow

Drshtim sakarunam - a look of kindness

Iti stotum - thus to praise

Vanchan kathayati - desiring says

Bahavani tvam - o Goddess you

Iti yaha - he who

Tadaiva - at that same time

Tvam tasmai dishasi - You grant him

Nija sayujya padavim - that state of identity with You

Mukunda brahm endra sphuta makuta nirajita padam - the same state as was gained by Vishnu Brahma and Indra by the bright waving lights of their diadems.

Arati - the ritual waving of lights.

"O GODDESS, YOU..." AND "MAY I BECOME YOU"

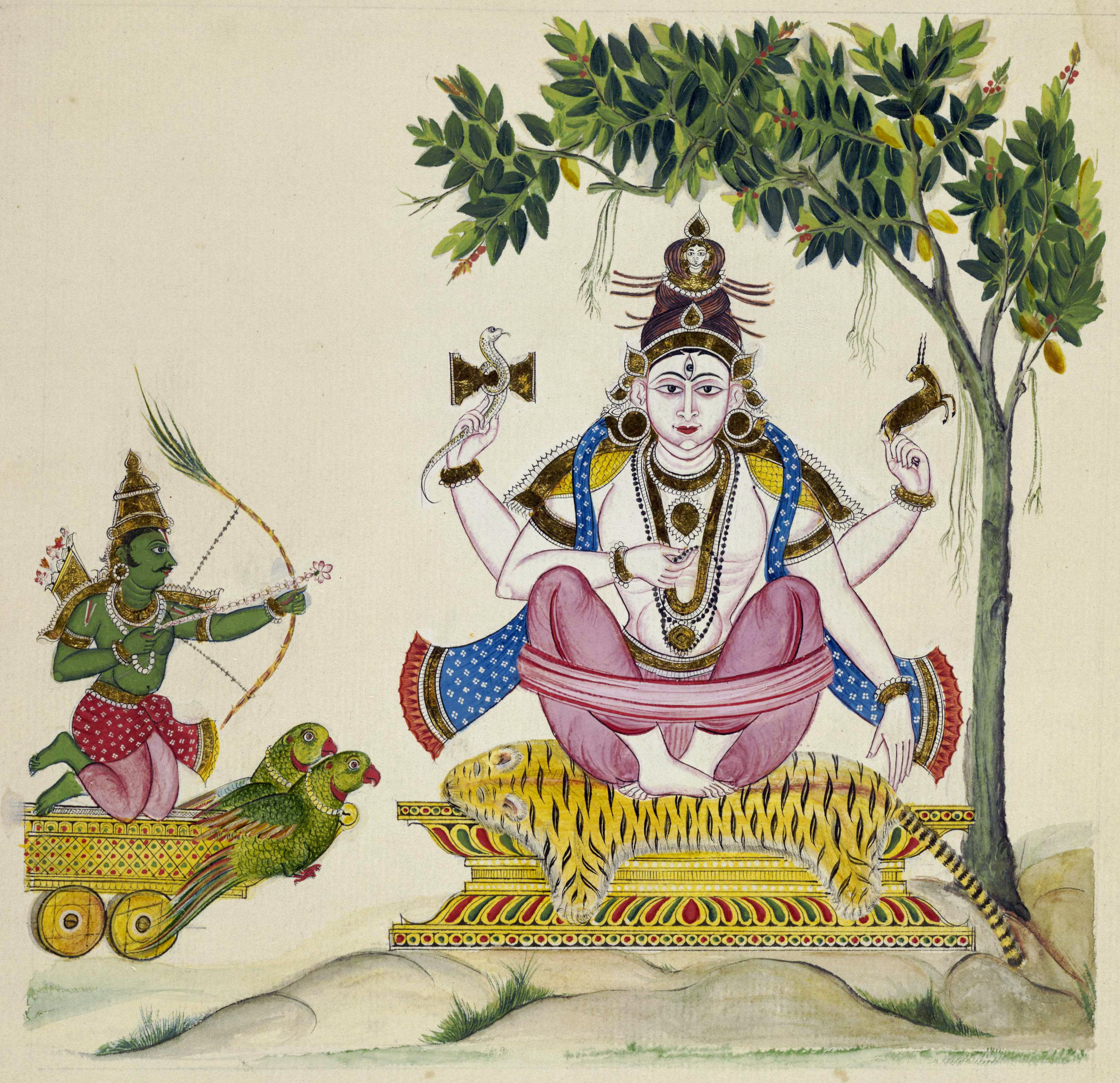

Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva perform Puja, bowing to the Devi with their shining crowns.

Advaita is the cancellation of duality.

The intentionality of linking Self and non-Self is greater than prayer - greater than the relativistic worship of the three gods.

The intentionality of prayer is more important than the brute act of prayer.

Worship is not necessary, even before the Goddess grants sayujya ("that state of identity..."), which is better than grace.

In the Vedic context, Brahmins and gods are elevated by their actions and made fit to worship the Devi.

Here, however, a "Dravidian child" without merit is the subject.

As if it were word-wisdom's ocean of nectar, flooding from out of Your heart

Offered by one who is kind, which, on tasting,

This Dravidian child, amidst superior poets, is born a composer of charming verse."

This verse transcends the Vedic puja (sacrifice) by Vedanta, which does not concern itself with ritualism.

Even just the desire to know Yoga will take you beyond the Shabda Brahman of the Brahmins.

The crest-jewel is the Numerator.

(Shabda Brahman is the Absolute (Brahman) as sound. ED)

Before the sentence is uttered, the boon is granted by the Devi.

This is the highest teaching of the Upanishads.

The three crowns of the Numerator gods are shedding some light on the hypostatic (positive) side

But, when you utter that sentence, you wish for the light of the Absolute Devi to descend on you.

This is none of your relativistic Vedic praise of a divinity.

The very intention to understand the Absolute makes one greater than all the Brahmins of the world.

-

-

Intentionality is respected above all relativistic prayers.

The light of the boon is complete - also having the Numerator factor included in it - and becomes the Absolute.

Hypostatic values are added as being secondary.

It occurs even before the sentence is completely uttered.

Otherwise, nothing new has been said.

"Your Numerator value is so great, that the lights which I light in the temple are as nothing. My lights are all relativistic - but Your light is Absolute."

Here, one goes to the Devi with humility, in the presence of the Absolute.

As soon as You can say the words Bhavani Tvam ("let me become you.."), at that very moment, (the intentionality implied), the boon is immediately given.

Even if a man simply has the intention to know the Absolute, then he is a superior man.

The point here is that the intention is more than the act.

When you say: "Please be kind to me", before the words are out of your mouth, the boon will be granted.

The Tri-Murti (3 gods) with their shining crowns, even when waved in honour of the Devi, are not of the same calibre as the devotee who asks for the blessing of the Devi - "Bhavani Tvam" - to become the Devi.

See the philosophical dictionary and read these definitions ten times.

(See B.A.F. Fuller of the University of California. Uberweg's is the best Dictionary of Philosophy).

There are the three gods of the Vedas with their fabulous crowns.

So the Absolute Devi belongs to a higher order than these.

When You accept many grades of truth, You are hedonistic and relativistic. Their crowns shine very brightly, but are simply included in the Absolute.

"I, You...", at that moment she says: "Do not say anything more, I have already granted You the greatest boon I have to give".

It is the intentionality which is the most important thing in the Absolute.

The act is not the most important thing.

(See Brentano's explanation of intentionality.)

(Brentano is best known for his reintroduction of the concept of intentionality to contemporary philosophy. While often simplistically summarised as "aboutness" or the relationship between mental acts and the external world, Brentano defined it as the main characteristic of mental phenomena, by which they could be distinguished from physical phenomena. Every mental phenomenon, every psychological act has content, is directed at an object. Every belief, desire etc. has an object that they are about: the believed, the desired. Brentano used the expression "intentional inexistence" to indicate the status of the objects of thought in the mind. The property of being intentional, of having an intentional object, was the key feature to distinguish psychological phenomena and physical phenomena, because, as Brentano defined it, physical phenomena lacked the ability to generate original intentionality, and could only facilitate an intentional relationship in a second-hand manner, which he labeled derived intentionality. ED)

This is the difference between relativism and Vedanta.

Vedic ritualism must build up to final point. (It does not attain it in one lightning flash, like Vedanta. ED)

The three gods are waving lights with their glorious crowns - this is a reference to temple worship - not Advaita.

These are the three gods known to Vedic Brahmins.

The lustre of their crowns represents their Numerator value, but even the lustre of these crowns cannot vie with the beauty of the Devi, which is a laser ray of a superior order.

Intentionality - to be devoted to the Absolute is richer than the hedonism and relativism of the Vedas.

One must know where Veda ends and Vedanta begins.

Vedanta is concerned with salvation.

Vedic luxuries are dull, like sleeping in the morning (tamasik),

or active, like hunting at five o'clock in the morning (rajasik),

the third is like Tennyson writing poems (sattvik).

They are like Brahma, Vishnu and Indra.

Hebraic Knowledge - to see the truth prevail - Ethics, Morality.

Whether they say it or not, everyone loves Absolute Truth.

So, to teach appreciation of Absolute Values is the highest calling and any such teacher will be reputed a great man, even if he remains hidden.

Sankara tells you about the distinction between Vedas and Vedanta and rises above good and evil.

He uses Tantric language, thus rising above the criss-cross divisions of language and custom - and it is these that are the causes of tribalism.

So Sankara is the Numerator Value for the Hindus.

He provided a philosophy with a place for the pantheon of Hindu gods.

The verse says that these crowns are lighting the feet of the Devi.

But the Vedantic devotee is visualising the totality of the situation.

The combined light of the three crowns of these three greatest gods only serves to light up the feet of the Devi.

Your intention is tantamount to understanding.

Before you even finish the sentence, the full beauty of the Absolute will descend upon you.

Subject and predicate are interchangeable.

"Bhavani Tvam.." = "O Goddess, You.." as well as "Let me become You.."

The whole grace has descended on the worshipper just because of his intentionality and thereby he becomes identified with the Devi.

Another version:

- O Goddess, You

- On me, Your servant

- Confer

- Gracious regard

- Thus intending to adore when one begins

- Saying. "O Goddess, You..."

- That same moment

- You confer on him

- Your proper unified state

- That state adored by waving of clear ritual lights of the crowns of Vishnu, Brahma and Indra.

The crowns have diamond tips of light and they bow to the devotee, because he has become the Absolute.

Shakespeare does the same thing in making Shylock a tragic hero - he is more sinned against than sinning.

HOW TO SHOW THIS IN A FILM:

Indra, Varuna and others should be told as they leave, that out there is the one they should prostrate to.

He sees only magenta glory, the third eye, the crescent moon etc.

This is a repetition of the same image throughout, with appropriate music etc.

The boy who was a Vidyarthi has now become a Yogi (Sankara himself).

The Absolute is ready to be kind to you, and you should be ready to be overwhelmed.

An elderly disciple should tell the temple-goers that if they go to a certain tree, they will see a saddhu (wandering ascetic) who has realised the Absolute Goddess.

"More than asked for boon": people are thirsty on a hot day, suddenly a terrible downpour comes.

SAUNDARYA LAHARI - VERSE 23

- Details

- Written by Patrick Misson

- Parent Category: Content

- Hits: 14874

SAUNDARYA LAHARI

VERSE 23

RELATIVITY IS REVISED TO YIELD ABSOLUTE ORTHOGONALITY

RECIPROCITY WITHIN A QUATERNION

त्वया हृत्वा वामं वपु-रपरितृप्तेन मनसा

शरीरार्धं शम्भो-रपरमपि शङ्के हृतमभूत् ।

यदेतत् त्वद्रूपं सकलमरुणाभं त्रिनयनं

कुचाभ्यामानम्रं कुटिल-शशिचूडाल-मकुटम्

sarirardham sambhor aparam api sanke hrtam abhut

yad etat tvad rupam sakalam arunabham trinayanam

kucabhyam anamram kutila sasicudalamakutam

The other, I surmise, became absorbed also; therefore,

This your form, having three eyes and bent by twin breasts,

Wearing a curved, crescent-bedecked crown, became of magenta glory.

In this verse Parvati, the wife, appears to be devouring her husband alive. When this act of mutual absorption or cancellation attains to its full limit, what remains of Shiva, in vague outline, is the crescent moon and three eyes, immersed in the pale magenta halo or glory of the Goddess. On the part of the Goddess, what remains of the eternal feminine principle is the twin breasts, which are so ponderous, weighed down by the responsibility of motherhood, that they make her body recumbent. Her own body is completely dissolved in terms of an all-pervading magenta, dispersed in infinite space and thus made equally magenta in content everywhere. It is as thin and tender in consistency, in existential terms, as the mathematical crescent of a subsistential order, against which the vaporous cloud of colour is to be cancelled out. The three eyes are retained as belonging both to the onlooker as well as to the one looked upon, interchangeably and indifferently. It is the third eye, through which the thinnest aspect of the vertical parameter is to pass as an eternal inner witness, which is common to both Shiva and Parvati.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS WITH STRUCTURAL DIAGRAMS RELATED TO THIS VERSE FROM SAUNDARYA LAHARI/NOTES.

Tvaya hrtva vamam vapah - by You absorbing the left (half) of the body

Aparitrptena manasa - unsatisfied in mind

Sharir ardham shamboh - the half of the body of Shiva

Aparam api - the other also

Hrtam abhut -

Yad etat tvad rupam - this which is Your form (resulting thus)

Sakalam aruna bham - wholly of magenta glory

Trinayanam - three eyed

Kuchabhyam anamram - slightly bent, recumbent, by virtue of twin breasts

Kutila shashi chudala makutam - wearing crescent-bedecked curved crown

She does not abolish, but cancels.

Magenta and the crescent have homogeneous status.

Her form becomes completely magenta, with three eyes.

Three compartments are abolished into the quaternion.

The whole ground becomes magenta and homogeneous.

The Devi, with the left half of her body, absorbs half of the body of Shiva; then, not content with that, she absorbs what is left.

Then she becomes magenta-coloured.

Her breasts are described as being bent in a figure-eight.

The Guru describes the breasts as a figure-eight which is part black and part white and gives a magenta colour when rotated quickly.

The Guru says: "Today I am feeling guilty that there would be changes; that I am putting proto-language into the verses. But it is not so: You have to use it."

Sankara has used a colourful, schematic language.

So here the Devi has completely absorbed Shiva, She has a crown with a crescent moon, three eyes, is magenta in colour and Her breasts are bent - but NOT bent by their weight, as the pundits state.

.

Another version:

TRANSLATION

- By thee absorbed

- The left (side) of the body (has been absorbed by You)

- With discontented mind (still unsatisfied)

- Of Shiva, half the body

- Also the other (counterpart) - (something remains)

- I do surmise (or doubt)

- Became also absorbed (she encroaches into the remaining half)

- This which is (given here, this which)

- Your (present, resultant) form

- Of glowing magenta colour / having three eyes

- By the two breasts somewhat recumbent

- Decorated by the bent crescent moon crown

(Bent crescent moon decoration - headgear)

Shiva is eaten up by the Devi because she represents ontology first.

She is real, he is conceptual.

Thus She has the crescent moon, which is the traditional crown or headgear of Shiva, as a final, conceptual, decoration.

It does not matter if Shiva is there at all. Shakti is given primacy over Shiva because ontology is the natural basis: travel from what you know to what you do not know: from Shakti to Shiva - this is the methodology of Sankara's Vedanta.

The whole of theology in the western world moves between Plato and Aristotle.

(Plato will tend to give primacy to ideas, while Aristotle will give more value to ontological factors. ED)

See Bergson on the reality of colour and Russell on the relationship between metaphysics and mathematics.

The crescent moon, which is the traditional decoration of Shiva, is the resultant of that form which has absorbed the body of Shiva.

Here the male and female have interpenetrating reciprocity.

Again, we have the cancellable version of Shiva and Shakti.

THE DEVI - FROM THE ALPHA POINT TO THE HORIZONTAL IS PHYSICS.

THE DEVA (SHIVA) - FROM THE OMEGA POINT DOWNWARDS VERTICALLY IS METAPHYSICS.

Sir Edmond Whittaker says that the structure of the universe was in the mind of God before it was created.

Eddington says: "if you put me in a room with a piece of paper, I shall predict the next eclipse".

Along with Pythagoras, they recognized the structure and the form which is clinging to it.

So, these men are conceptualists.

James Jeans says that God is a mathematician.

So, theology is coming back to science.

Ethics is derived from a philosophy and that philosophy must be scientific, i.e. pulling together the world of the observables and the calculables.

These two worlds must be put together into one.

See Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, the Alexandrian school (Plotinus), the Christian Mystics, the middle ages, Copernicus, Darwin, etc.

(See also Aldous Huxley's "The Perennial Philosophy").

"I want to put order into my thoughts and it was finally Narayana Guru who put me on the track to the Upanishads.

So let the children of the drop-outs start a new movement.

Vedanta is unique because it is ordered and the terms defined.

We just want to put things in order and arrive at a notion of the Absolute.

Yesterday, the crescent moon is bent, now the breasts are also bent.

She encroaches on the body of Shiva.

Virtuality is common (in principle), thus, it is the left side.

Actuality remains - the Devi represents ontological, down-to-earth actual reality, Shiva represents the mathematical implications of this actual reality.

She wants to absorb that right half as well.

In so doing, she has to sink into Herself. But she gets the third eye because she cannot absorb all of the mathematical aspect without some of it showing: the eye represents the calculable, transcendent Omega Point.

She also has his decorative crown, with a thin crescent moon, which is curved.

So, the crescent moon is the Bindhusthana or central locus of meditation.

How are the breasts bent? Because left and right are treated as virtual and actual breasts, on the left and right sides of the horizontal axis, respectively..

The Devi is encroaching from her existential side, devouring first the left, or virtual side; then the right, or actual side, leaving only the Numerator of the crescent and third eye.

The two breasts cancel out into a Yin-Yang pattern.

There are two references to "bent" - anamram, kutila.

sarirardham sambhor aparam api sanke hrtam abhut

yad etat tvad rupam sakalam arunabham trinayanam

kucabhyam anamram kutila sasicudalamakutam

Kutila shashi chudala makutam - wearing crescent-bedecked curved crown

He wants a curve introduced to the crescent. "Somewhat recumbent" suggests bringing it into a circle, thus we arrive at Yin-Yang.

(There is a curve to the crescent moon, which is combined with the curve of her slightly bent waist to form a Yin-Yang structure within a circle. ED)

The Guru says: "Am I going beyond the limits of speculation? In Sanskrit literature, you have to be free in your speculations; it is not read like a telephone book. For example: "moon-like face" refers to lustre in Sanskrit and does not mean round or pancake-like.

So, you have to know the Sanskrit classics in order to interpret this in the tradition of Sankara and Kalidasa.

So I am taking the liberty of putting the breasts into a Yin-Yang schema.

You have to be prepared for this through reading other works of Sanskrit literature. Otherwise you will not be able to interpret the verses."

METHODOLOGY FOR MAKING A FILM

Gradual negation of the negative: construct the positive Absolute by reducing the negative into positive.

The Absolute is androgynous.

Parvati first eats up the left half of Shiva.

Classical and popular images of the "Half-Woman God" form of Shiva (Ardhanarishvara).

Then, not content with this, she devours the right half as well.

Then, bent by the weight of the breasts, she is of aruna (magenta) colour.

So here, the emphasis is on the negative ontological side.

Integration of plus and minus results in the Absolute.

The bending suggests a figure-eight.

You cannot abolish Shiva completely, the third eye and the crescent remain.

The Alpha Point is abolished into a figure-eight.

So this is a double principle of negation and construction.

She begins on the left side because that is easier for Her; after that, She can enter into the positive side.

This is an iconographic ideogram, a kind of protolanguage.

The figure-eight can mount and becomes aruna (magenta) when it passes the horizontal axis. Still the third eye is left, as the value of meditation, and the crown as the source of the Ganges.

The minus side becomes positive and the magenta colour results.

Another version:

TRANSLATION

- Absorbed by You

- The left side of the body

- With mind not fully satisfied

- The half of Shiva's body

- The other counterpart also

- I surmise

- Became absorbed

- By virtue of which

- This (this world)

- Your form

- Having magenta glory

- Third eye

- Bent by breasts

- Having a crescent moon-adorned crown

Not fully satisfied, She goes from the less important to the more important, in a methodological order. There is first a horizontal reduction from the virtual side (1)

- then from the vertical (3).

Monomarks representing Shiva remain as the third eye and the crescent moon.

In the diagram below She begins eating from the left.

.

.

(1) from the virtual side across to the actual side, when she finishes the horizontal axis, then she shines on the negative vertical

(2) Going from left to right is bilateral symmetry. Going from top to bottom is transfer symmetry.

(3)The resultant of the cancellation is the magenta colour - since the two bodies have cancelled.

Then, the third eye implies the Devi has become verticalized.

Bent by the weight of breasts: (See the reference in Verse 80 to the waist as so thin as to need to be bound up by Kama Deva with three vines.)

To get to the bottom of this iconic ideogram, we have to abolish the waist into a sinus curve.

Then the crescent and crown are the final aspect of Shiva - it is all the representation he needs - the principle or monomark remains over the whole scheme.

SAUNDARYA LAHARI - VERSE 24

- Details

- Written by Patrick Misson

- Parent Category: Content

- Hits: 13139

SAUNDARYA LAHARI

VERSE 24

PLUS AND MINUS COMPENSATION

DOWNWARD NORMALIZATION

THE TRANSCENDENCE OF PHENOMENAL FUNCTIONS IN BRACKETS

जगत्सूते धाता हरिरवति रुद्रः क्षपयते

तिरस्कुर्व-न्नेतत् स्वमपि वपु-रीश-स्तिरयति ।

सदा पूर्वः सर्वं तदिद मनुगृह्णाति च शिव-

स्तवाज्ञा मलम्ब्य क्षणचलितयो र्भ्रूलतिकयोः

jagat sute dhata harir avati rudrah ksapayate

tiraskurvann etat svam api vapur isas tirayati

sada purvas sarvam tad idam anugrhnati ca sivah

tavajnam alambya ksana calayitor bhrulatikayoh

Brahma creates the worlds, Vishnu protects, Shiva destroys;

Negating all this and his own body, the Lord fades out,

Thus what results; Shiva who has eternity for prefix (Sadashiva)

He blesses, obeying the orders derived from your instantly vibrating eyebrow-twigs.

This verse, placed correctly in its epistemological perspective, views the same process as in the previous verse, but from a partially reversed perspective. Here we go from the side of causes to the side of effects. Thus, when we say that Brahma creates, the reasoning process normally travels from the cause or source of creation, which is below, to a higher level where the effects of creation are more pluralistic or multiple. This function of creation, represented by Brahma, can be structurally imagined to be like a tree. When this process of creation has gone far enough, the divided multiplicity of entities creates a horizontal firm ground for human actions and reactions to operate upon, through which individuals could promote themselves further in the vertical scale of values. This is the Vishnu-world of graded value-stratifications, cutting through which at right angles, each man or woman attains to life's fulfilment, according to their desires or deserts. In every sentient being capable of aspiring for spiritual progress one could imagine a vertical parameter cutting through the horizontal sleeping Vishnu-world to the vertical Shiva-world.

Beyond these Vishnu stratifications of graded life-purposes lies the pinnacle point from which Shiva descends, flame in hand, to burn the various value-cities, so as to bring balance again between creation and its inevitable opposite. Shiva, conceived as the pinnacle of the situation, is not a mere abstraction, but participates in existence through Parvati, with whom he shares his own body as the androgynous god Ardha-nari-isvara (half-woman-god). Their relation here is one of back-to-back double correction, and not one of mere horizontal importance. Thus participating with his own counterpart at the O Point and sharing the horizontality, though only through the magenta of the previous verse, he is here represented as being interested in abolishing even this thinnest of absolute substances. This is what is indicated in the second line where Shiva fades out from the second to the third dimension. As a result, he attains to greater heights of abstraction and generalization where his more exalted condition justifies the term Sadashiva applied to him, rather than just "Shiva" who is an agent that destroys the second-dimensional world.

If this process of exaltation of Shiva should be accentuated further, even the various value worlds would stand in danger of being abolished altogether, leaving nothing by which the human soul could attain its purpose. Life has to be significant, if nothing else. Any philosophy that does not retain this, as the last residue at least, and deprives life of all its significance or purpose, becomes a philosophy that is empty of consolation and cancels its own raison d'être. Vedanta does not aim at such an ultimate bankruptcy of significance or purposes as might be claimed by other philosophies more thinly speculative, such as lukewarm "maybe, maybe not" attitudes, or systems which do not go beyond paradoxes to purposefulness in life.

It is to avoid this total bankruptcy of purpose that the "eyebrow-twigs" of the Goddess have the all-important role of saving the situation. She does not show her concern in any overtly gross terms, but Shiva can see from her "instantly vibrating eyebrow-twigs" that she is highly concerned about the possible destruction of all her progeny in the form of created beings. She, in principle, is in charge of all of them, and she cannot deny her own proper function. The world has to go on as it was in the beginning, now and forever, without end.

The blessing in the fourth line is to be treated as the combined operation of the function of the rays of Shiva and Parvati together, with no element of separation, in keeping with Advaita Vedanta.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS WITH STRUCTURAL DIAGRAMS RELATED TO THIS VERSE FROM SAUNDARYA LAHARI/NOTES.

Jagat sute dhata - Brahma creates the world

Harihi avati - Vishnu preserves

Rudra kshapayate - Shiva destroys

Tiras kurvan etat svam api vapur - negating this and even his own body

Isah tirayati - the lord fades out

Sada purvaha - he who has eternity for prefix

Sarvam tad idam - all that results or remains here

Anugrhnati cha - he also blesses

Sivah tava jnam alambya - obeying Your order

Kshana chaliyator bhru lati kayoh - from Your instantly vibrating pair of eyebrow-twigs

See Bergson's image of entering Notre Dame cathedral, rather than observing it from the outside.

The Absolute is not an object, but the result of cancellation.

Items of value, endless series of items of value strung on a string or vertical parameter, are equal to God.

Whatever a yogi is doing, he sees the Absolute always.

The Absolute is a universal value, just as magenta it is a Universal Concrete. (see Hegel).

(For Hegel, only the whole is true. Every stage or phase or moment is partial, and therefore partially untrue. Hegel's grand idea is "totality" which preserves within it each of the ideas or stages that it has overcome or subsumed. Overcoming or subsuming is a developmental process made up of "moments" (stages or phases). The totality is the product of that process which preserves all of its "moments" as elements in a structure, rather than as stages or phases.

Sadashiva (supreme Shiva) is the highest Omega point, but has to be cancelled against the Devi at the Alpha Point.

Brahma creates, Vishnu sustains, and Mahesvara (Shiva in his relativistic horizontalized aspect) destroys.

He triumphs as a mathematical entity and escapes from his body.

Sadashiva (the Supreme Shiva) is even beyond the Omega Point and is eternal.

He takes orders at once from the vibration of Her eyebrows.

-

.

.

Total negation is denied validity.

You cannot say that Brahman (the Absolute) is nothing.

This means that there has to be some compassionate content to the Absolute.

Shiva is just mathematical, with no compassion.

- He creates the world (the god Brahma)

- Hari (Vishnu) saves (it) (sustains it)

- Rudra (Shiva) destroys (it)

- Cancelling this

- Your own body also (Devi's)

- The lord causes to disappear

- Having the word eternal as prefix to it (Sada-Shiva) (Sadashiva is different from just Shiva)

- Shiva all these blesses too

- Having respected Your (Devi's) orders

- Momentarily moved

- By creeper (slim) eyebrows

The function of horizontalising - Rudra (Shiva) coming to destroy things -

Brahma creates them.

- Brahma creates the world

- Vishnu saves

- Shiva destroys (See Verse1)

- Inverting (??) this also his own body

- The Lord (Ishah) makes all fade out

- The one with eternity for prefix (Sada purvah)

- All of this state (arrived at by the previous line)

- He bestows benediction upon also / Shiva (normal)

- Resorting to Your mandate

- Instantly vibrating (at great frequency)

- Instantly vibrating (at great frequency)

- Of the twin eyebrow-twigs

The trinity of the three gods - Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva (in his demiurge aspect as the destroyer) is Vedic, but the negative function of Sadashiva is Vedantic.

The three functions belong to the phenomenal aspect.

But percepts can be conceptualised, so the degrees of conceptualisation and perceptualisation in the schemas or structures can vary.

Thus here, we put the three functions in the Denominator to avoid two schemas.

The negative side contains the horizontal principles - the zone of ontological richness - while the Numerator is ontologically indigent and teleologically rich.

.

You can have gods at different conceptual levels.

The Absolute as Paramatma (the Supreme Spirit) - Sada Shiva - is impersonal.

As Shiva, he is a god - the normal Absolute - and as Isa (Lord), he is concerned with human affairs.

So, Shiva can be placed at several points on the vertical axis.

Burn the seed, so that it can never sprout - that is Sadashiva.

The eyebrows of the Goddess are at the negative limit

She is the normalizing negative limit.

Respect and devotion are due in this order: "God, Guru, Father, Mother, martyrs to Truth, those who aid justice": these are all the grades of devotion in this world, as stated in the Darsana Mala of Narayana Guru, Chapter 8, Bhakti Darsanam, Vision of Contemplation, Verse 9 & 10. Parampara Bhakti - a hierarchy of devotion.

Spiritual teacher, father, mother,

Towards the Founders of Truth, and

Towards those who walk in the same path;

And those who do good to all -

What sympathy there is, is devotion here,

While what here belongs to the Self Supreme is the ultimate

Sadashiva is "Obeying Your orders" - this means he is looking to the Devi for permission to function.

Shiva and the Devi are something in two perspectives, the relation is interchangeable.

Here the value is the same, it is only seen from two perspectives.

Here, no matter how great Shiva becomes, Devi's influence is still there, as the eyebrows.

This is called reconstructing the Absolute.

Double assertion starts with Shiva,

Double negation starts with the Devi.

By double assertion we attain the Absolute, but there is the slightest bit left over and this is the benefit of Value.

If there is nothing, then there is nothing to write.

But there is something - value - and that is called Brahman.

Value is the irreducible factor at the core of the Absolute.

The point is that the only thing that is left is the horizontal

- the Devi's eyebrows and the vertical Sada Shiva.

2) The control (?) of the Devi on the Numerator is not inoperative, however.

3) The eyebrows vibrate to show everyone in split-second alternations of light and darkness. The three gods must be shown here.

4) Bracketing - thus bringing in the phenomenological epoché.

(Some years after the publication of his main work, the Logische Untersuchungen (Logical Investigations; 1900-1901) Husserl made some key conceptual elaborations which led him to assert that in order to study the structure of consciousness, one would have to distinguish between the act of consciousness and the phenomena at which it is directed (the object-in-itself, transcendent to consciousness).

Knowledge of essences would only be possible by "bracketing" all assumptions about the existence of an external world.

He called this procedure epoché.

Husserl then started to concentrate on the ideal, essential structures of consciousness.

The metaphysical problem of establishing what kind of reality we perceive was of little interest to Husserl in spite of his being a transcendental idealist.

Husserl proposed that the world of objects and ways in which we direct ourselves toward and perceive those objects is normally conceived of in what he called the "natural standpoint", which is characterized by a belief that objects materially exist and exhibit properties that we see as emanating from them.

Husserl proposed a radical new phenomenological way of looking at objects by examining how we in our many ways of being intentionally directed toward them, actually "constitute" them (to be distinguished from materially "creating objects or objects" . ED)

5) A construction process and reduction process.

6) The pure Absolute remains, but not without the control of the vibrating eyebrow-twigs of the negative principle.

Show magenta glory circulating; the top is smoke, the bottom is dust.

Show the other gods as well, graded in realism to the most horizontal, then fade it back into vague terms, finally attaining a fluorescent glow as the vertical axis,

So there is a kind of "breathing" between the vertical and horizontal aspects.

SAUNDARYA LAHARI - VERSE 25

- Details

- Written by Patrick Misson

- Parent Category: Content

- Hits: 35317

SAUNDARYA LAHARI

VERSE 25

THE ABSOLUTE, BOTH TRANSCENDANT AND IMMANENT

ALPHA AND OMEGA MODES ARE REVERSIBLE

TRANSCENDING THE THREE MODES

भवेत् पूजा पूजा तव चरणयो-र्या विरचिता ।

तथा हि त्वत्पादोद्वहन-मणिपीठस्य निकटे

स्थिता ह्येते-शश्वन्मुकुलित करोत्तंस-मकुटाः

bhavet puja puja tava caranayor ya viracita

tatha hi tvad padodvahana manipithasya nikate

sthita hy ete sasvan mukulita karottamsa makutah

Their worship of you, o consort of Shiva, would alone be worship

Offered to your twin feet; it is indeed thus when they do so,

Standing eternally beside your gem-decked footstool, joining bud-like their hands well above their crowns.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS WITH STRUCTURAL DIAGRAMS RELATED TO THIS VERSE FROM SAUNDARYA LAHARI/NOTES.

Trayanam devanam - of the three gods

Triguna janitanam - originated from the three nature modalities

Tava sive - of Yours, o consort of Shiva

Bhavat puja puja - their worship of You would alone be worship

Tava caranayor ya viracita - as offered to Your twin feet

Tatha hi - in spite of it being so

Tvad padodvahana mani pithasya nikate - standing beside Your gem-bedecked footstool

Sthita hi - standing indeed

Ete sasvat - eternally these

Mukulita karottamsa makutah - joining bud-like their palms well above their crowns

The Goddess above is teleological.

The footstool is ontological.

Teleological is the Devi above.

Ontological is the footstool below.

The gods join their hands above their heads like buds.

The three Vedic gods worship the Devi, with their hands folded above their crowns.

"The gods, born of the three Gunas, do worship at Thy pearly footstool".

"Puja-puja": that is the real Puja (worship), which is offered at the feet of the Devi.

They are standing there eternally, because the Devi is eternal.

The existential footstool is at the bottom of the vertical axis - it is the basis of ontology.

It is Absolute as opposed to relativistic worship.

One must transcend the three Gunas or nature modalities (this is implied).

Puja.

- O Goddess, consort of Shiva

- The homage (puja) rendered to the three gods

- Who have their origin in Your three Gunas

"These gods of the Numerator side, who have their origin in the Devi's qualities (gunas) are continuously worshipping Your footstool as the real ontological source.

Real puja is that being done by the three gods who are standing by Your pearly footstool, with their hands raised to their crowns in adoration".

The crowns are false - only the footstool (Existence, lower even than the Devi's feet) is held more important than the three hypostatic crowns.

The totality of the Absolute is represented as existence.

The footstool is the square root of minus-one - it is more important than the three gods.

Ontological value and beauty of the footstool are emphasized.

The verse says: "That puja at the stool is puja" and the stress is on existence, rather than subsistence.

Another version:

- Of the three divinities

- (Who are) born of the three gunas

- Which are Yours

- O Shivé (consort of Shiva)

- Would be the worship (the real worship) (puja puja)

- The worship

- Of Your twin feet

- That which is applied

- As such indeed

- What takes place near thy pearly footstool

(That puja which is applied to thy feet is indeed the puja)

- Standing as they do indeed

- These three gods eternally

- Their palms joined as final decoration of their crowns

"SAT" (EXISTENCE) IS HERE REVEALED AS THE MOST IMPORTANT TERM OF VEDANTA.

This is in contrast to Satkarya-Vada: where primacy is given to effect as against cause. ED)

Phenomenology turns everything upside down and stresses existence rather than essence.

The knobs on the crowns of the three gods worship the footstool of the Devi.

Why not worship the Omega Point?

In Vedanta, it is Sat, existence, which is emphasized.

Sankara is not asking you to do puja to the Goddess.

The puja of the three gods is the real puja - standing by Your footstool with their hands fixed on their crowns.

(This is a language based on the Vedic mystical language, you have to understand this if you want to understand these verses.)

They do not put a glorious crown on the head of the Devi - the footstool represents the ontological basis of reality.

This is the point of Vedanta, as revalued in this verse.

In Europe, the language of phenomenology is somewhat similar to this.

Vedanta already has the phenomenological aspect in view.

Revaluation consists of hypostatic gods worshipping the ontological basis found in the footstool.

Now there are many, many pages to be read.

The three gods, eliminated in the previous verse, reappear again in this verse.

They are put outside as worshippers of the Goddess.

The phenomenal world is put in the Denominator, doing the puja of the gods to the Numerator Devi. The negative worships the positive.

Another version:

- Of the three gods

- Born of the three modes - (triguna)

- Yours, O Parvati

- Only that worship would be worship (puja puja)

- Of Your twin feet

- That which is thus performed

- That is so indeed

- Near the pearly footstool bearing Your feet

- Standing as they are indeed

- There eternally

- With hands held worshipfully joined above their crowns

There is participation between the physical, the relative and the conceptual.

They participate through the footstool.

Three gunas (nature-modalities) are hiding in the feet of the Goddess and the three gods are born from these.

The conditioned worships the unconditioned.

This is the proper relationship between the lower and the higher Brahman.

Through ontology, we can proceed to teleology.

Go from what you know to what you do not.

Various forms of puja.

This is a revaluation. Vedic teaching reaches the culminating point of Vedanta. In the film, some guru has to teach wisdom to the Vedic Gods.

Vedanta is more than religion or philosophy - it is lifted above them.

First we have to make the most ontological contact with the footstool of the Devi - that is holy enough for You.

Her feet represent an absolute value and the pearly footstool gives an idea of the value of the feet that rest upon it.

The Vedic Gods have got everything except tyaga (renunciation or detachment from the merely glamorous aspect of life, or relinquishment of ends and benefit-motivation in active life).

"Hear now from Me, 0 Best of the Bharatas (Arjuna), the

settled conclusion about relinquishment (tyaga), (which)

relinquishment indeed, 0 Best of Men (Arjuna), has been

well known as of three kinds:

the act of sacrifice, gift and austerity should not be

relinquished; each should indeed be observed; sacrifice,

gift and austerity are the purifiers of rational men;

but even these actions should be done leaving out

attachment and desire for result; this, 0 Partha

(Arjuna), is My decided and best conviction."

(Verses 4, 5, and 6)

ED)

The three gods can understand this by worship of the footstool.

The highest part of the Vedas tries to catch up with the lowest part of Vedanta.

It is jeweled, which confers dignity on it.

This is the cancellation between hierophany and hypostasy.

See in the Gita, there is a tree with roots below and above..

These are ensembles - see Cantor.

There is one-one correspondence.

(Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor was a German Mathematician, best known as the inventor of set theory, which has become a fundamental theory in mathematics. Cantor established the importance of one-to-one-correspondence between the members of two sets, defined infinite and well-ordered sets , and proved that the real numbers are "more numerous" than the natural numbers . In fact, Cantor's method of proof of this theorem implies the existence of an "infinity of infinities". ED)

SAUNDARYA LAHARI - VERSE 26

- Details

- Written by Patrick Misson

- Parent Category: Content

- Hits: 14058

SAUNDARYA LAHARI

VERSE 26

NATARAJA - VERTICALIZED FUNCTIONS

NEGATIVE BECOMING

THE FOURTH-DIMENSIONAL SHIVA

विरिञ्चिः पञ्चत्वं व्रजति हरिराप्नोति विरतिं

विनाशं कीनाशो भजति धनदो याति निधनम् ।

वितन्द्री माहेन्द्री-विततिरपि संमीलित-दृशा

महासंहारेஉस्मिन् विहरति सति त्वत्पति रसौ

virincih pancatvam vrajati harir apnoti viratim

vinasam kinaso bhajati dhanado yati nidhanam

vitandri mahendri vitatir api sammilita drsa

mahasamhare'smin viharati sati tvat patir asau

Brahma regains his pure quintuple nature; Vishnu becomes passionless;

The God of Death destruction meets; the God of Wealth becomes bankrupt;

The great Indra becomes functionless, with half-shut eyes;

In this great doom, he sports, o constant spouse, Your Lord alone.

Between the three verses, 24, 25 and 26, there is a two-sided dynamism that we can recognize as a world process on a certain kind of world ground, which the philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita (VII, 18) calls avyakta (unmanifested). Everything has a vague, amorphous or mathematical status at a given time, anteriorly. It assumes a colourful real form with different perspectives at a middle stage and in a final stage re-absorption again takes place. Besides the Bhagavad Gita, Cartesian Philosophy can also understand this cyclically alternating process with these three phases as taking place between what it calls res cogitans and res extensa. Thus, we could have the same basic reference in terms of Cartesian correlates instead of by description. Res cogitans would be a vertical perspective, and res extensa the alternative horizontal version of the same. Bergson would prefer to distinguish these as time-like and space-like counterparts. Vedanta is familiar with a similar theory, having a double perspective in the manner of viewing the status of the elementals. Professor O.Lacombe describes this theoretical process, called pancikarana, as simply as possible:

"The great elementals do not enter as such into the composition of individual realities, but undergo first a sort of shaking-up which is called quintipartition - panchikarana. Each of them is divided by the creator into two parts, and one of these two halves again into four parts. Each one of these quarters is then mixed with the half that has been left intact of each of these four elements.

It thus results that each element composes itself thereafter as follows: one half element pure, plus one-eighth of each of the four other elements. It is these composite elements which serve for the constitution of individual things.

The dominant proportion of the primary element safeguards its authenticity. But the adjunction of the other elements explains the participation of things with all other things and explains certain anomalies of perception."

(O. Lacombe, "L'Absolu Selon le Vedanta" (Paris 1937), our translation.)

.

When the elementals remain in their pure self-transparent form, they consist of tanmatras (entities-in-themselves). Manifestation, in realistic terms, takes place when these rays are brought under a perspective by which they attain different degrees of opacity or transparency between themselves.

In the world of light, various interference effects occur when double-polarized light is brought into interplay; depending on the angle of incidence or refraction and due to diffraction or dispersal of light, various interesting interference figures could be seen. There is a mesh or lattice which obstructs or permits light waves of different wave lengths to pass through crystals, depending on whether the obstruction is placed at right angles or not.

Without entering into the intricacies of such optical phenomena, we shall merely say that Vedanta has long adhered to the theory of pancikarana. Horizontally perceived, the elementals show a heterogeneity between the five of them, but when the tanmatras, as basic elemental units, are rearranged serially and vertically, after being subjected to the processes called "quintuplication" or "quintipartition" - they attain to a certain homogeneous and serial continuity and transparency along the vertical axis. Elementals, when remaining in a crude state, give a horizontal outlook to the world of manifestation. When subjected to quintuplication, they become transparent in themselves. In television, it is two sets of waves intersecting at right angles, on the basis of an orthogonal matrix or lattice consisting of small rectangular units, that results in a picture.

Even in chemistry we can either see the elements arranged in a vertical series according to the periodic law, or we could study the properties of chemicals by reactions in the laboratory. The periodic law gives us a verticalized perspective, while the actual properties of chemicals are presented to the senses as a horizontalized reference.

Verse 24 is a reference to a positive creative process, but Verse 26 presents the same picture as a negative process. In Verse 24, the balancing factor comes from the Devi's eyebrow-twigs, while in Verse 26, the Devi herself lends her reality to keep her husband continuously alive, even as a thin parameter. In Verse 25, we find a double picture, as seen through two kinds of translucency: one in which the horizontal prevails over the vertical and one in which the vertical prevails over the horizontal. Creation and dissolution are brackets facing opposite ways, traversed by the parameter that represents pure becoming, independent of time or space.

With these preliminaries in our mind, we have to understand that, in line one, the figure of Brahma, as a member of the Hindu trinity, is the first to be put into the melting pot, because of the quintuplication to which all the elementals are going to be subjected in the negative process that is being represented in this verse. In the case of Vishnu, the effect of such a negative process is to make him passionless, because the passions absorb each other without finding horizontal expression. He is subjected to a state of neutralization or normalization at the central stratum, wherein he alone is operative. When we apply the same cancellation of tendencies to the principle of death, we see that the very meaning of death cancels itself out by the double negation involved. Indra is a god at the stratum where hypostatic values prevail. He is also struck by a certain verticalized immobility, by which all his horizontalized tendencies are balanced against their opposites. The result is that he remains immobile, as if in a picture, neither opening his eyes too wide to show any curiosity, nor fully unaware of the interests with which he is surrounded.

This state of dissolution into the original amorphous transparency of the elementals in themselves is called pralaya (merging back into a pure and primary formless absolutist status). This picture is not unlike that of doomsday, except that in the idea of doomsday the dissolution has a futuristic or apocalyptic status. The deluge of doomsday could be treated as complementary to the present image, if we like. The prophetic religions give primacy to a doomsday or a day of judgement, but the antediluvian picture is also a part of the Old Testament. Whatever the theory involved, all that we have to know here is that, in the form of an amorphous matrix, or in the form of crystals once again dissolved, we can get different perspectives, three of which are given in Verses 24, 25 and 26. Many other perspectives could also be visualized without violating the requirements of the Science of the Absolute. When we take a normalized position, the result is the one stated in the Bhagavad Gita, where Krishna tells Arjuna that the kings and the armies are not there except in Brahman, and that they are not going to be created thereafter either. This is the perfectly normalized picture, based on which we could have as many varied perspectives as we like, all of which, however, have to be put within the limits indicated here without contradiction. A crypto-crystalline homogeneous rock is as good a rock as a porphyritic one (full of different kinds of well-formed crystals put together). The Absolute is the matrix or mother liquid for all of them.

What we have to note here is whether the process is a positive or a negative one. The status of the Absolute, represented by the vertical parameter, remains unaffected and the same throughout, as in the case of the entropy of the universe tending to be a zero or attaining to a maximum. Brahman, the Absolute, as a correlating thread passing through all possible values, is familiar to us in the Gita (VII, 7) which says that everything in the universe is threaded through by Krishna, the absolute Value of all values. Narayana Guru also identifies the Absolute as God and compares him to the highly mathematical dimension called the depth of the sea in his "Daivadasakam" (Verse 4). "Fire cannot burn this (parameter), nor water wet it....the sword does not cleave it" as the Gita says (II, 23, 24). This eternal and changeless parameter or line is what represents the Absolute as nearly as we could think of it in any concrete terms.

We have added the word "pure" in brackets in the first line to show that it is a negative process that is taking place here, rather than one of positive creation. By saying that the God of Death meets destruction, we are only indulging in a tautology. We can neither improve death nor degrade him in any way. It just marks the O point by being doubly corrected.

Concerning the reference to the God of Wealth becoming bankrupt: wealth functions by getting and spending, which are horizontal processes. Without these two actions, the bank becomes sealed to the public, although this does not mean that the bank no longer has any money.

Tan-Matra , a subtle element, or rudiment of elementary matter, of which five are popularly enumerated, viz: sabda, sparsa, rupa, rasa and gandha, from which are produced the five gross elements. (tat, that; matra, element.)

Daivadasakam (A Prayer for Humanity)

by Narayana Guru

1

0 God, as ever from there keep watch on us here,

Never letting go your hand; You are the great Captain,

And the mighty steamship on the ocean,

Of change and becoming is Your foot.

2

Counting all here, one by one,

When all things touched are done with,

Then the seeing eye (alone) remains,

So let the inner self in you attain its rest.

3

Food, clothes, and all else we need

You give to us unceasingly,

Ever saving us, seeing us well-provided.

Such a one, You, are for us our only Chief.

4

As ocean, wave, wind and depth

Let us within see the scheme

Of us, of nescience,

Your glory and you.

5

You are creation, the Creator,

And the magical variety of created things.

Are You not, 0 God,

Even the substance of creation too!

6

You are Maya,

The Agent thereof and its Enjoyer too;

You are that Good One also who removes Maya too,

To grant the Unitive State!

7

You are the Existent; the Subsistent and the Value-Factor Supreme

You are the Present and the Past,

Add the Future is none else but You.

Even the spoken Word, when we consider it, is but You alone.

8

You state of glory that fills

Both inside and outside

We for ever praise!

Victory be, 0 God, to You!

9

Victory to You! Great and Radiant One!

Ever intent upon saving the needy.

Victory to You, perceptual Abode of Joy!

Ocean of Mercy, Hail!

10

In the ocean of Your Glory

Of great profundity

Let us all, together, become sunk,

To dwell there everlastingly in Happiness!

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS WITH STRUCTURAL DIAGRAMS RELATED TO THIS VERSE FROM SAUNDARYA LAHARI/NOTES.

The vertical axis is not abolished.

Virincih pancatvam vrajati - Brahma regains his pure quintuple nature

Harihi apnoti viratim - Vishnu becomes passionless

Vinasam kinaso bhajati - the God of Death destruction meets

Dhana daha yati nidhanam - the God of Wealth courts bankruptcy

Vitandri mahendri vitatir api - the great Indra becomes functionless

Sammilita drsha - with half-shut eyes

Maha samhare asmin - in this great doom

Viharati - he sports

Sati - o constant spouse

Tvat patihi asau - Your lord alone

Dhana daha yati nidhanam - the God of Wealth courts bankruptcy

dhana daha refers to the God of Wealth - Kubera.

Vinasam kinaso bhajati - the God of Death destruction meets

Kinaso refers to Yama, the God of Death.

Virinci is Brahma, the God of Creation.

Here all the functions of the gods and the fourteen Manus (lawgivers) cease to be operative "in the great dissolution" - the destruction which is the function of Shiva, as represented by his dance.

All of the horizontal factors are disintegrated.

The Devi remains chaste - only the vertical factor remains - the relationship between Shiva and his chaste spouse, the Devi; thus Shiva remains - the integration of positive and negative - of Shiva and the Devi - is never lost.

Destroy Samsara, the relativistic horizontal.

Shiva dances with the Devi, because of her chastity; horizontal factors are abolished.

The vertical Pati - Sati (Shiva-Shakti) union avoids final dissolution.

There is reciprocity between Sati and Pati (the faithful wife and her spouse).

Another version:

TRANSLATION

- Brahma (five-fold) inertness gains

- Vishnu (Hari) attains cessation from passion (or desire)

- Death accomplishes its final (function) extinction

- The God of Wealth goes bankrupt (to his death)

- Even the incessantly active 14 light principles of Indra's domain (of high Numerator value - the 14 Manus - the fortnight)

- With shut eyes (half asleep - as if drugged)

- In this great time of dissolution

- O chaste one (This is the key line)

- Your Lord alone

- He sports (and is happy - when every phenomenological and cosmological function is destroyed.)

.

According to "quintuplication" (panchikarana) the five elementals, when mixed together in certain proportions will produce all of the things in creation.

The functions of creation, proper to Brahma, cease(in this great time of dissolution and Vishnu, as pleasure principle, attains to a passionless state. He too is abolished - as his function of preservation is abolished.

The God of Death, Yama (or Shiva) accomplishes his final function.

The God of Wealth goes to his death - i.e. loses his money.

The chastity of the Devi is the key here - She is so true to her husband that when she becomes verticalized (chaste), then all of the horizontal functions disappear.

(The universe is, by definition, horizontal - subject to creation, preservation and dissolution - and dissolves when the pure verticality of the union between Shiva and the Devi prevails. ED)

This verse is an example of psycho-dynamics - the dynamics of the structure are revealed.

The structure is universal - the sun (Shiva) and water (Devi) cancel out and produce mangoes on a tree.

You have to participate in the structure of something dear to You.

All of the fourteen Manus, who are hypostatic functionaries, close their eyes and go out of commission.

(Manus are the progenitors of mankind, who are said to have been the very first kings to rule this earth. During each age of mankind, 14 Manus are said to appear, one after the other, who manifest and regulate this world. ED)

This is not good for them, but it is good for Shiva.

For, when Parvati is completely verticalized at the Alpha Point, then he too can become completely vertical.

Even the numerator world of the intelligibles ceases to have these functions - thus it says, "with shut eyes".

These horizontal relativistic gods, who are functionaries of the Vedic context, become inoperative.

Here a great period of dissolution has come and Shiva is in charge of destruction - and he is right.

"Only Your husband enjoys all of this - because You, O Devi, are chaste; Shiva is happy."

Now Shiva can dance. Shiva's destructive factor involves drawing or absorbing everything into the vertical axis.

(Proto-language is best found in the Saundarya Lahari - Narayana Guru's language is even more mathematical - more compressed, like a billiard ball. Sankara has not pressed it so hard, it is more loose.)

The key to this verse is why all the gods become functionless.

The inert bones of my hand are ready to move at the command of my mind, which is a theoretical entity. What is the connection between mind as agent and the arm as that which functions?

This means that mind participates in matter; but in what way?

This is a basic question in philosophy.

(The problem of mind and matter was dealt with by René Descartes in the 17th century, resulting in Cartesian dualism, and by pre-Aristotelian philosophers. A variety of approaches have been proposed. Most are either dualist or monist.

Dualism maintains a rigid distinction between the realms of mind and matter. Monism maintains that there is only one unifying reality, substance or essence in terms of which everything can be explained. ED)

.

Here the gods as functionaries are cancelled out in a certain order.

Only with this in mind can you understand why sati is the key word. (sati means "a constant" or "chaste" wife.)

There is a vertical axis between Parvati and Shiva.

.

Shiva dancing - Nataraja.

Shiva is "sporting" while all the gods are cancelled out.

This means he is dancing the dance of Nataraja.

It is for itself, in itself, of itself - it is pure action or transmission.

(See Bergson for the difference between transportation and transmission. Transportation is horizontal; transmission is vertical. ED)

Contrast a truck taking stones to a radio sending a message.

THE TRUCK IS HORIZONTAL - THIS IS TRANSPORTATION

THE RADIO IS VERTICAL, WHICH IS TRANSMISSION

A child refusing to go to a stranger's hands is both horizontal and vertical - its hesitation is a figure-eight.

A frightened deer forgetting to eat grass and running away is horizontal

- the neck is a sinus curve.

A girl hesitating to be made love to, consenting and refusing at the same time, makes a sinus curve, a figure-eight.

The idea of this verse is to reveal a vertical parameter, with the Alpha and Omega Points, which exhibits cancellation, complementarity etc.

This chastity of the Devi (sati) represents constancy and thus belongs to the Absolute.

Why does everything go out of commission? Why do the gods dissolve?

To neutralize everything into the Absolute means to schematize and abstract.

(In other words, to verticalize. The structural methodology used by Nataraja Guru is a process of abstraction and generalisation. ED)

The situation in this verse represents pure (vertical) consciousness.

In this spiritual world of value are all of the relativistic Vedic Gods: Brahma, Vishnu, Death, Wealth and the Manus, and in this order they are all eliminated, that is, verticalized.

Only the chastity of the Devi at the Alpha Point - which is independent - remains. All other functions have been eliminated.

This can be seen as a line of electricity, with an electric bulb at the Alpha Point, like the seed at the base of a plant.

Shiva is sporting; in himself, by himself, for himself - that is, like your mind.

The fires which have been burning in the fourteen worlds of the intelligibles (of the Manus) have gone out.

Contingency and necessity have cancelled out.

This is where the Vedas end and Vedanta begins.

(The Vedas deal with the horizontal world of contingency and necessity; Vedanta deals with the vertical only - this is the difference between Karma Kanda - the Vedic domain of action - and Jnana Kanda - the Vedantic world of wisdom alone. ED)

The movement of the Denominator is horizontal - like transportation.

The Numerator movement is vertical, like transmission.

Brahma is out of commission, Vishnu is trying to kiss Parvati, all the lights are going dim, the God of Wealth is going bankrupt, the pure vertical axis remains, then a light which dims into negativity, with Shiva sporting.

Shiva has to be a Numerator - a flame has to burn all the brighter if it is the Numerator aspect of chastity.

The functional aspects of the Alpha and Omega are clarified here;

so Alpha and Omega do not cancel.

This is a verticalization into the noumenal state within brackets.

Shiva is sporting, when everything else has been destroyed.

This is all due to the Devi's chastity.

The lesser truth is always hidden by the greater truth.

A list of gods is abolished in a certain graded order of values.

The universe is here reduced to noumenal content.

(An expanding universe = red shift,

a contracting universe = violet shift.)

Magenta exists in the negative zone between infra-red and ultra-violet.

This is a picture of the great dissolution of the universe and the phenomenal aspects of the universe are demolished in a certain order - from the most horizontal towards the vertical.

(Brahma could therefore be seen as the most horizontal, then Vishnu, the gods of death and wealth, then a more vertical Indra and finally Shiva. This seems to the Editor as only roughly correct, but the manuscript seems clear. ED)

The horizontal is demolished from the ontologically rich Alpha Point at the negative lowest point of the vertical axis.

Another version:

TRANSLATION

- Brahma loses his five-fold expanding function

(Viriñci)

- Vishnu attains disinterestedness (Hari )

- The God of Death has destruction for his own counterpart

(he vertically destroys himself, as an event )

- The Wealth Giver has become bankrupt

- The great Indra is put out of function by dispersion also (Mahendra)

- With half-shut eyes (from too much enjoyment)

- In this great act of destruction (or dissolution)

- Sports

- O constant spouse (Sati)

- Your Lord alone

Sati (the Devi's constancy) is the key. Without this constancy he, Shiva, would have evaporated long ago.

The secret is in the absolute constancy of the wife.

Shiva gets the privilege of sporting only because of the lower brackets.

(There are upper and lower brackets on the vertical axis between which the cancellation or love between Shiva and the Devi takes place, it is so purely absolutist and vertical that there is no risk of horizontalization - or so it seems to the ED)

Verses 26, 27 and 28 are to be taken together.

This is a case of surviving evil by double assertion.

He survives without double negation.

HOW TO SHOW THIS IN A FILM:

In this verse we have an equation of Self with non-Self. This is a neutral position or matrix - use the crystal here, to show equalization.

Double negation - "Not, not" is more affirmative than a mere "Yes". Begin with Verse 27 as in the notes on the previous page, then go to Verse 28.

.

Double Negation - show a man in a well kicking his feet in the water and saving himself.

Let it be Eros: show the milk ocean churning and the drinking of poison.

.

..

Eros - Kama Deva.

.

.

.

Then show the woman sprinkling water on his eyes, he survives by double assertion, the man jumps into the water and saves himself by arm strokes alone.

Whatever the number of electrons, they cancel out with the nucleus; the "H" of Planck remains unaffected: c.f. "La Structure Moléculaire".

.

.

(The Planck constant (denoted H, also called Planck's constant) is a physical constant that is the quantum of action in Quantum Mechanics. The Planck constant was first described as the proportionality constant between the energy E of a photon and the frequency V of its associated electromagnetic wave. This relation between the energy and frequency is called the Planck relation. ED)

The parity here is reflected in molecular structure.

Quintuple functions are vertically abolished.

The vertical axis is not abolished.

Where the vertical and horizontal cross there are nodes = colour or sound.

Psychedelic space has a one-one correspondence with cybernetic space.

- Two-sided cybernetics.

- The cybernetic retroaction of inner space.

- Homeostasis - one-one correspondence and parameters.

- Conic space with two parameters.

- Upward and downward logarithmic spirals.

-